Nothing was a greater source of pride and satisfaction to a man of means in the early days of our nation than his hunting dogs. There was no greater thrill than following those baying hounds, astride his favorite stallion, as they rambled across hill and dale in pursuit of the furry quarry of the hunt. But sometimes the hunt doesn't go well. Old Reynard the fox eludes the hounds; B'rer Rabbit makes it snuggly into the briar patch; or the weather conspires to keep the spoor of the game from the noses of the hounds. What would you do if your prized hunting pack failed in the quest, particularly when you had bragged too much to your hunting companions? If you were the master of an iron plantation, you might think of flinging your sorry pack of hounds into the fiery pit of the blazing cauldron of the furnace. The legend says that was what happened at old Colebrook Furnace. "But all this happened long ago; and many a storm of windy snow had capped the hill and filled the dell, since Flora's chase was news to tell."

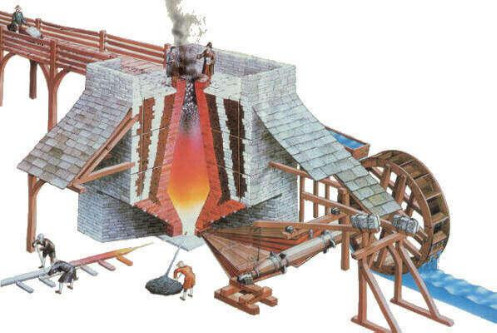

A major early industry in colonial America was the production of iron, much needed for the tools, implements and weapons essential for survival both in the cities and on the frontier. Pennsylvania became a leader in the industry because of the relative abundance of the three necessary ingredients: iron ore, timber from which to make charcoal, and limestone. It took hard work by many hands to make iron. It was a risky business that often failed, but with luck the owner/investors could become rich men, so there were always entrepreneurs willing to take on the risks. Such a man was Robert Coleman, who owned interests in many iron furnaces and forges in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. He built the Colebrook Furnace on Conewago Creek, about six miles southwest of Cornwall, in 1791. It was originally named Mount Joy Furnace. It came into the possession of Robert's son Thomas Bird Coleman and then in turn to his son William. Operations at the furnace were abandoned by 1860. It was common practice for the owners/speculators of a furnace to hire a man of more technical skills to oversee the actual production of cast iron. Robert Coleman thus hired a man by the name of Samuel Jacobs to be the first ironmaster of Colebrook. This story is about Squire Jacobs and his hunting hounds.

"Howbeit, this devil's labor rolled back on the Squire in floods of gold. Gold and hunting and potent drink and loud-tongued girls, that grin and wink over the flagon's dripping brim, these were the things that busied him. Strong of sinew but dull of mind, he blustered round like a winter wind. You could hear his laugh come on before while his hounds were off a mile or more; and in the wassail he stormed and roared, clashing his fist on the groaning board, or clutched his trulls till their young bones bent, and they shrieked at his savage merriment."

Samuel Jacobs may have been a good maker of iron, but he was a cruel and vicious man, a drunkard and a lecher. The master of an ironworks was akin to a king in his kingdom. His word was law. Jacobs's workers feared him, as he flogged or fired them for any transgression real or imagined. His servant girls were subjected to unwanted advances. The only living beings he showed rare kindness to were his hunting hounds, especially the dog named Flora, the white leader of the pack. She was the best of the dogs, and loyal to him in spite of his ways.

"One winter night when half the world was drowned in snow, whose billows curled above all landmarks - when the breeze stung like a swarm of angry bees, and made a traveler wild and blind - the Squire, half-drunken, left behind some neighboring revelers, to essay across the fields his homeward way." A sober man would have stayed put on such a wintry night, but Squire Jacobs had consumed enough spirits to dull his senses, and so he set off for home in the teeth of a raging December storm. How far he had to go we know not, but it didn't matter, for he strayed from his course and in due time became hopelessly lost and exhausted. He stopped to rest, for a moment or two he thought, hoping that when daylight came he would once again find his way. But the drink he consumed and the tiredness of his aching body soon caused him to drift off to sleep and to start down the slow path of freezing to death.

Back at the master's mansion home at Colebrook, Flora, the great white hound was troubled. Never away from Jacobs's side when he was near, she would lie in pine for him whenever he was absent. As the evening grew late, she paced the floor and scratched and whined at the door, but the servants ignored her. Later they would tell how she wailed a howl that could only be of anguish and leaped through the glass of the front-room window to the ground below. Then she was off into the night, her deep baying sound disappearing into the storm. It took Flora some time, but she found the Squire where he lay in stupor. "She reached the Squire, a rigid heap; already the thick, fatal sleep was heavy on him; and the snow was rising, like a tidal flow, around his person." Flora dug the snow from his sides, and barked him into sensibility. Then half-leading, half-dragging him to his feet, she led him homeward, Jacobs holding to her to stay upright as he leaned into the winter wind. Somehow the two made it back, Flora barking and scratching at the manor-house door until the servants within roused and opened it to them.

"Long after that, he knew no more until he wakened in his bed, with Flora resting her white head between his knees, and her soft eyes fixed on his own, serenely wise." Who knows how long Samuel Jacobs took to his bed, but to surprise and disappointment of many, he slowly recovered his health. Was he grateful to Flora for saving his life? Perhaps in his own unfathomable way, but his outward disposition towards others changed not a bit. Among his other habits, he resumed the hunt, riding as of old behind the pack of hounds, with Flora in the lead as always. He delighted in bragging about his hunting dogs and horses, and in taking nimrods and other city folk along on the hunting rides to hear the hounds bay and see them flush the quarry from the brush to the gun. He most likely made heavy bets on how well his hunters would perform. It was on such a hunt that our story dwells. "Such was the favored day that bent above the Squire, as forth he went, noisy and boastful as of old, to show some city friends how bold his horses were before a fence; and how the depths of every sense were stirred when all the hounds gave tongue, and down the hills the whole hunt swung, with whoop and halloo, bark and bay, and o'er the country scoured away."

But the day was not to be favored. The Squire's fine pack of dogs seemed to sulk from the beginning. They seemed to hold back on the chase, as if they simply weren't in the mood to hunt that day. The Squire and his huntsmen didn't spare the whip or the curses as they drove the dogs along. Even Flora, always proudly and excitedly in the lead, often followed the pack, she too seeming to have no heart for the scent of the fox. Jacobs and his huntsmen soon decided that one of his visiting citymen must have somehow poisoned his hounds, at least enough to make them act as they did, and thus bring embarrassment to their always overly-prideful and boastful host. "Why, zounds! Matthew, what ails these cursed hounds? I know not, sir, replied the Whip, Unless some scoundrel chose to slip a drug into their feed last night, to do your promises a spite." Matthew, the huntsmen, urged Squire Jacobs to turn back from the hunt, knowing the dogs would make no run that day. But no, turning back was not his way, and so the dogs were driven on. Even when the old Red Fox they hoped for rose from the brush almost under Flora's nose, the pack still seemed not to care. The Squire flew into a rage, taking the whip from the Huntsman and using it himself as he rode back and forth around and even over his fine dogs. "Amid the cowering dogs he dashed, rode over some, cursed all, and lashed even Flora till her milky side with trickling crimson welts was dyed. He raved and punished while his arm had strength to do the smallest harm."

A rational man would have taken his dogs home and gone to hunt again another day. A cruel impulsive man like the Squire would have been satisfied to have punished the dogs as he did and then to limp them home. But no, that was not enough. In his imagined humiliation - those city men had laughed at his and his hounds' disgrace - he thought to punish the poor curs even more. He ordered his huntsmen to drive them on. "Drive, sir? Where?" The Squire's answer was quick to come. " 'Where? Why to Colebrook, down the glen. I'll show these town-bred gentlemen, If my dogs cannot hunt so well on earth, another hunt in hell' bawled the mad Squire; and all the beast in his base nature so increased, that he could crown the deed he sought with laughter brutal as the thought."

Slowly but surely it sank into the conscience of the huntsmen and the guests and all assembled the mad plan of the Squire. There was protest, there was refusal, but Squire Jacobs threatened his men with the whip now and the loss of their jobs as well. The guests, wanting no part of this foul deed, took their leave. But the huntsmen were cowered by the Squire, though wanting no part of it either, they lamely drove the dogs along the way back to the flash and spark of the belching furnace stack. Surely he would have had enough spoke the huntsmen to each other; surely he would see the folly of his wild plan. But no, once the Squire made up his mind, nothing it seemed could change the course. Then he summoned the firemen and gave his command. "Come here, you drones, and work a spell! Look to your furnace! Can you tell what needs a fire so dull and slack? Feed it, you sluggards, with this pack!"

Again the men held back, protesting and trying their best, to their great credit, to turn his course, but the Squire would have none of it. "Do as I order!" he bellowed, and the men had not the heart to disobey. One by one, the hounds were seized by the firemen, taken to the loading deck at the top of the furnace stack and consigned to the flaming cauldron. "Into the flames with howl and yell, hurled by the rugged firemen, fell that pack of forty. Better hounds . . . never could Cornwall boast." The pack was gone. Only the great white dog, leader of all the hounds, remained. Flora, who had saved her master's life that cold winter's night, in spite of his pitiless ways, alone remained. Surely she would be spared the horrid fate of the others. At first the Squire didn't notice her there alone in the dark, until her blind loyalty caused her to move towards him, wanting only to be by his side, as she had been so often over the years. When he saw Flora there, he hesitated not a moment before telling the men to throw her too into the blazing pit. Again the men hesitated, but a crack of the Squire's whip turned them to the great dog. Flora bared her fangs, she crouched and growled. The men backed away. Dropping his whip, the Squire softly called his dog to him. Instantly her menacing posture melted away, she came to her master, tail wagging, the look of a loyal hound in her eyes. In an instant, the Squire took her in his arms, and even as she turned her head to lick his face, "Sheer out he flung her. As she fell, up from the palpitating hell came three shrill cries, and then a roll of thunder. . . The Squire reeled backward. Long he gazed 'Was it a fancy? If you heard, answer! What was it? - that last word which Flora flung me?' Answer came, as though one mouth pronounced the name, and smote the asker as a rod; 'The word she said was - God, God, God! ' "

The deed was done. All left the scene of the horror, and the Squire started his homeward ride, but life would never 'er be the same. Deserted by even the few friends he may have had, and even more detested by employees and staff of the ironworks, the Squire could soon find solace only in even more drink. His health quicky spiraled downward. He would sit for hours, despondently, speaking only to something invisible to the eyes of others that seemed to lie by his feet, his hand from time to time stroking the unseen creature. It was about that time that folks began to report mysterious howlings in the night, although others said these were the anguished groanings of the Squire himself. Soon he took to his bed and one day he asked that the bed be moved so he could once more look upon the fiery blast from the Colebrook stack. In a while he spoke the name of Flora and then screamed aloud that the hounds were coming for him. The servants ran to the window but of course could see nothing but the belching of the furnace. When they looked back, the Squire was dead. "Here they all come, the hellish pack, pouring from Colebrook Furnace, back into the world! Oh, see, see, see! They snuff, to get the wind of me! They've found it! Flora heads the whole, whiter than any snows that roll O'er Cornwall's hills, and bury deep the wanderer in blissful sleep. Ho, mark them! We shall have a run before this ghastly meet is done! Now they give tongue; they've found their prey! Here they come crashing - all this way - and all afire! And it is I - weak as I am, and like to die - who must be hunted? With a bound he reached the floor, and fled around; once, twice, thrice, round the room he fled, then in the nurse's arms fell dead."

Reports of the phantom baying of the hounds of Colebrook were heard from time to time for many years, but the reader should keep in mind that "all this happened long ago; and many a storm of windy snow had capped the hill and filled the dell, since Flora's chase was news to tell."

[ Whether this story happened at all, or if it did, whether or not Samuel Jacobs was actually the Squire of the tale, is open to speculation. Robert Coleman, noted as the first millionaire iron master, built Colebrook Furnace in 1791 near the furnace at Cornwall, in which he also owned a majority share. Coleman was related by marriage to Cyrus Jacobs, who was an investor in several iron works, and may explain why Samuel Jacobs, the son of Cyrus, was hired as ironmaster at Colebrook. But perhaps Coleman was the villain of the legend. Another version of the tale can be found occurring not at Colebrook but rather at Cornwall Furnace, with one of the Grubb family as the culprit. The story as written above is largely taken from the 1876 poem by Philadelphian George H. Boker, among other references. Boker's poem is entitled: "The LEGEND OF THE HOUNDS by Geo. H. Boker in connection with OLD COLEBROOK FURNACE at COLEBROOK which lies at the foot of South Mountain Range of which CORNWALL ORE HILLS form a part." All quotations in the story above are taken from this poem, in which the Squire remains unnamed. I also thank my brother, Daniel Graham, noted Pennsylvania iron historian, and Stephen Somers, Administrator at Cornwall Furnace Historic Site, for invaluable information.]